You are here

A life-long commitment to independent reporting

By Sally Bland - Dec 11,2016 - Last updated at Dec 11,2016

A Country of Words: A Palestinian Journey from the Refugee Camp to the Front Page

Abdel Bari Atwan

London: Saqi, 2008

Pp. 285

For the title of his memoir, Abdel Bari Atwan chose a line from a Mahmoud Darwish poem: “We travel like other people, but we return to nowhere… We have a country of words.” This is emblematic of Atwan’s preoccupation with his lost homeland as well as his profession as a writer. The book’s subtitle sums up the course Atwan’s life followed, partly by design, partly by luck, and partly by virtue of his being Palestinian.

Growing up in Deir Al Balah and Rafah refugee camps in the Gaza Strip, Atwan lived in several Arab countries and worked diverse jobs before emerging as an internationally acclaimed, UK-based journalist, editor and political commentator. While he became famous (infamous, in some quarters) for his 1996 in-depth interview with Osama Ben Laden, his greatest achievement was founding the first, truly independent, pan-Arab newspaper, “Al Quds Al Arabi”.

In an engaging style, fact-filled yet intimate, Atwan covers a lot of ground in his memoir, from the basics of the Palestinian cause and half a century of tumultuous events, to the Arab scene in London, his family and their return visits to Gaza in the 1990s. He knows how to capture a situation with well-chosen details and readily shares his personal convictions and feelings. Though the second half of the book is filled with prominent names and events, Atwan’s account of growing up in Gaza is actually the most charming part of the narrative. His first memories are of his mother’s storytelling which warmed long, dark, winter nights as he and his siblings huddled on the floor around a wood fire. She told folk tales, ghost stories and more. “It was the stories from her past, though, that affected us most deeply and we loved to hear about Isdud, the small Mediterranean village she and my father lived in until the Nakba”. (p. 15)

Like others in Gaza’s camps, his family’s economic situation was dire, and they were plagued by recurring Israeli attacks, but Atwan also portrays the lighter side — family togetherness, youthful escapades and a variety of larger-than-life camp personalities.

One is struck by the number of times Atwan landed in a new place virtually penniless, but survived and acquired beneficial experience, based on sheer determination and the art of living on next to nothing that he had acquired in childhood. After the 1967 occupation, there seemed to be no option other than leaving Gaza. He went to Amman intending to continue his education, but ended up sleeping on a roof and working in a factory and later as a driver. Though it proved impossible to continue his education due to lack of funds, he did acquire the valuable habit of reading. After two years, he left for Egypt, where he had relatives, and was able to finish secondary school in Alexandria, study journalism at Cairo University, and immerse himself in pan-Arab culture and politics. In retrospect, he credits Nasser’s generous pro-Palestinian policies for his degree: “Nasser’s vision had enabled me to turn my life around.” (p. 88)

But with regime change, his plans to do an MA at Cairo University were aborted. In 1974, the authorities refused to renew his visa, citing his student activism, including speeches and writing against Sadat and other Arab leaders. He had to leave Egypt quickly and by chance was offered a job driving a wealthy business man to Tripoli. “With just one bag and no money at all, I set off across the desert towards Libya and an uncertain future.” (p. 115)

For the rather harrowing drive, the businessman paid him a pittance, so he was reduced to staying in a “hotel” where three residents shared a mattress by sleeping in shifts. In Libya, he sold his first story but was soon frustrated by the lack of professionalism in the press, and moved to Jeddah where he worked for “Al Medina”. This led to a job offer with “Al Sharq Al Awsat” which took him to London.

Here ends the story of arriving penniless, but not of Atwan’s struggle to remain independent. His political differences with “Al Sharq Al Awsat” came to a head during the First Intifada, pushing him to resign and start “Al Quds Al Arabi” in 1989. Twenty-four years later, after publication of this memoir, he resigned his post as editor-in-chief because he feared the funding offered to resolve the paper’s financial crisis would impose political constraints on its contents. Instead, he started the electronic Arabic daily, “Rai Al Youm”. Judging from this memoir, Atwan is very capable of adapting to all sorts of circumstances, but Palestine and journalistic independence are issues on which he will not compromise.

Related Articles

Islamic State: The Digital CaliphateLondon: Saqi Books, 2015Pp.

Attachment to Palestine, and perseverance in the face of adversity, permeate Rawda Al Farekh Al Hudhud’s memoir, “The Woman of Yaffa”. While the original Arabic text has been published previously, this volume also includes an English translation, as well as many fascinating photos ranging from scenes of pre-1948 Yaffa to family members.

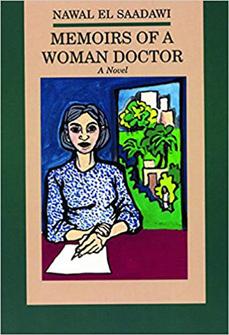

Memoirs of a Woman DoctorNawal El SaadawiTranslated by Catherine CobhamLondon: Saqi Books, 2019Pp.