You are here

Ludwig W. Tamari: A life well lived, a man well loved

By Marwan D. Hanania - Dec 21,2017 - Last updated at Dec 21,2017

Ludwig W. Tamari (1927-2017) lived a full life.

In fact, he lived an exemplary life. His “modus vivende”, to borrow a term he loved, was always optimistic, empathetic and inclusive.

Not once could you hear him utter a negative word about any living soul. He had a heart of gold and an accompanying intellect that was hard to match. “Blessed are the pure of heart”, says Matthew, “for they will see God” (Matthew, 5:8).

Surrounded by his loving family, Ludwig passed away at his home in Potomac, Maryland, on the night of December 7, 2017 at the age of 90.

He is survived by his devoted wife of 52 years, Myr Tamari (born Hanania); children Wahbé, Rula and Marwan; children’s spouses Vanda, Omar and Nadine; and seven grandchildren.

Thus ended a remarkable life lived to its fullest by an adventurous, cultured, resilient and indelibly tolerant man.

Abu Wahbé, as he is lovingly known to his friends and family, was born in Jaffa, Palestine. His family members were Arab Christians of the Greek Orthodox sect. Ludwig was born in July 1927 during the interwar period when Palestine was still under a British mandate.

His mother, Adela Malak, hailed from a prominent Palestinian family. Having befriended a German nurse, Adela asked the nurse to name the newborn child. The nurse’s choice fell upon the name Ludwig, in honour of her brother. Ludwig is an old Germanic name, a composite of two words: “Hluth” meaning “famous”, and “Wig” denoting “war”. Many great men were so named, from Beethoven to Wittgenstein.

Tamari was a lifelong pacifist, but he fought the good fight and succeeded in overcoming every trial and tribulation that life threw at him. In doing so, he lived up to the example of many of his namesakes.

“Waylunlil-maghlub” he sometimes wrote in his letters, a reference to the plight of the Palestinians.

“Woe to the Vanquished!”

He knew that plight full well.

A refugee from Palestine to Lebanon and Jordan, he became an exile a third time in America, due to the Lebanese Civil War and tough economic times in Jordan.

As if the protagonist in Thomas Cole’s famous paintings, “The Voyage of Life”, he took life by the horns and went wherever he needed to go to support his family, while all the while remaining a calm, strong, steady influence.

In short, he was a sturdy captain at the helm of a ship that had to cross the most turbulent waters.

Exiled from the shores of Jaffa by the Palestinian Nakba or catastrophe, his voyage took him to the urban environs of Beirut, to a then small, perhaps unpromising town of Amman in Jordan, and finally to Central and North America.

He encountered obstacles everywhere he went, but overcame every challenge.

Where others saw trouble, he saw opportunity.

As a creative, enterprising Christian Palestinian merchant in Lebanon and Jordan, he met with both support and opposition. As an émigré doing business in the United States, he understood that the path to integration and assimilation was not always smooth.

But like one of his namesakes, Ludwig Joseph Wittgenstein, Tamari understood that “the world is all that is the case”.

Politically, Tamari was a realistic moderate, although his realism was always undergirded by a deeply empathetic view of other human beings.

At a talk he gave at Cornell in 1956, Ludwig conveyed the typical fears of an exile living in America, but also expressed his unyielding confidence in the country’s democratic foundations: “America must be beyond reproach because she assumes the democratic leadership of the world,” he is quoted as saying by the Cornell Daily Sun. “Segregation in this country must not be compared with segregation in other countries, but America should be above them.”

His belief in America’s strength was reflected in a sound, but brave, decision to buy what was then an inconspicuous piece of land in Potomac from a farmer during a random drive through the wilderness of Washington, DC. Atop that land now sits his family’s home in one of the most prestigious locales in the world.

His “Lebensphilosophie”, or philosophy of life, was forward-looking. He took calculated and sometimes spontaneous risks and, more often than not, reaped the rewards of doing so.

Perhaps he had inherited this trait from his father, Wahbé Tamari, a successful Palestinian merchant.

Wahbé had been educated in Jesuit schools during the Ottoman period and eventually built a profitable citrus growing company and worked as a trader. He was also a philanthropist who contributed time and money to educational ventures and charities.

Together Wahbé and Adela raised six children: Abdallah, Joseph, Ludwig, Nina, Diana and Farah.

After receiving his primary and secondary education in Palestine, Ludwig attended the American University of Beirut in the 1940s and received an MBA from Cornell University in 1956.

Ludwig left Palestine with his family on May 15, 1948, the day the British mandate of Palestine ended. He moved to Amman with his youngest brother Farah. As a result of their combined efforts, the Tamari family business experienced significant growth. Through hard work and business acumen, the two brothers emerged as leading industrialists and traders in Jordan. They successfully imported and exported foodstuffs and raw materials such as sugar, rice, coffee, tea and vegetable oils.

Like their father, the two Tamari sons were diligent businessmen who had a long-term vision predicated on a sound understanding of regional politics and dynamics. The Tamaris bought land in the early 1950s in Marka and constructed a flourmill, banking on the expectation that Amman was a burgeoning city at the time where there would be a growing need for food. They then established a tea-packing plant and a facility that produced vegetable oils, again anticipating a rise in consumer demand for such products. The Tamaris also understood that Palestinian markets in the West Bank would naturally be cooperating with East Bank Jordanian markets in this newly evolving business environment. They cultivated strong relationships with the authorities in Jordan and with leading business minds throughout the region.

By the 1960s, the Tamaris were firmly established as major industrialists and traders. They soon diversified in the area of light industries, which included packaging. The family business continued to grow despite the challenges posed by the 1967 Arab-Israeli War and the 1975-1990 Lebanese Civil War. Eventually, Ludwig and Farah established the Tamari Trade and Industry Company, which exported sugar, food, vegetable oils and spices to Iraq.

During the 1980s, Ludwig moved to the United States and settled with his family in the small, scenic town of Potomac near the fabled Potomac River in Maryland. He continued to travel to the Middle East but also cultivated business ties in Honduras and Guatemala, trading coffee and cardamom.

In addition to his knack for business, Tamari was a scholar, activist and philanthropist. He wrote and published many articles in Arabic and English about the politics and history of the Middle East, anticipating some of the major developments that were to beset the region. Tamari knew and interacted with most of the key players in the Middle East, including many of the leaders of the region. He was moderate and always espoused reconciliation.

Although a Christian by birth, Tamari was well-versed in the Koran and in the Islamic tradition more broadly. His command of both English and Arabic was superior and reflected years of reading and learning. He could quote verses from the Muslim holy book and from the Hadith at will to explain or elaborate a particular point. He was also erudite in the areas of Western philosophy, antiquity, the histories and cultures of the indigenous peoples of the Americas, and in the history of Arab-Jewish relations.

Ludwig’s political views mirrored his views on life.

Among his many writings, Ludwig published a beautifully written article titled “The Declaration of Principles: Shock Treatment for Palestinians and Israelis” in Middle East Insight in 1993.

Rereading this prescient piece today in 2017, I recall a time when there was an active push for peace by men of his stature. The article calls for genuine efforts towards peace but warns that the journey could be easily set off-course by the wrong people. In concluding his article, Tamari exclaimed that “a tiny gesture of good will could arrest a flow of ill will” and called for courageous actions to build peace: “Let those with the will to give peace a chance, take that chance.”

Still Tamari understood the limiting nature of the peace process and the continued objectification of the Palestinians that it entailed. In a letter he sent me in 2005, he wrote that “now we are relegated from [the false claim of being] terrorists on the loose to the status of partners under the noose.”

He pieced together writings as if putting together a jigsaw puzzle, gradually collecting different clippings from newspapers and from his diaries, and pasting them on a single sheet of paper. From there, he would begin to write his essays. The end results were beautiful pieces that offered unique insights into Israeli-Palestinian politics and to the condition of the Arabs more generally. The pieces were teeming with important information and keen philosophical insights. They always displayed a broad understanding of what is going on in the region.

For our extended family, he was the primary starting point for any and all complex historical topics. You would start with him and he would guide you in the right direction. For me personally, he was absolutely instrumental in my growth as a human being and as a scholar.

Both my older brother Zeid and I followed in his footsteps by going to Cornell University, which is the best academic decision we took. In an uncanny coincidence, Zeid rented a room in the same house that Ludwig had occupied in Ithaca, NY, some 42 years earlier. After renting the room, Zeid stumbled upon a ledger that contained the names of all of the house’s prior occupants. When he got to the 1950s, he found the name Ludwig W. Tamari.

Together with his wife Myr, and throughout his life, Tamari was active in prominent circles to try to promote peace and reconciliation in the Middle East.

The couple also shared a passion for helping other people and opened their home to various charity organisations.

With their family, they patronised the Wahbé Tamari Kindergarten in Amman which, since 1973, has espoused a modern philosophy to develop the holistic capabilities of children.

Ludwig also provided scholarships to gifted students as they made their way through school and university. He helped everyone who came his way from a driver who was going through hard times to the employees of the Tamari Company, and even to lending the famed author Alfred Lilienthal his cabin in Lebanon so that the writer could have the solitude he needed to write one of his most famous works.

Ludwig was a strong, physically resilient man. He loved the outdoors and nature. As if sensing the kindness of this larger-than-life person, animals warmed to him and, as a consequence, the family kept pets for many years.

Abu Wahbé often spent hours doing hard laborious tasks outside his home in Maryland.

Well into his late 80s, he was still strong enough to shovel mounds of snow off his property. He also was an amateur artist and excelled in water painting, a passion he shared with Myr. Their beautiful paintings adorn the walls of their home in Potomac, in addition to works of indigenous art from all over North and Central America that Ludwig collected over many years.

Tamari lived a peaceful, productive, exemplary life. He died peacefully and will be missed.

Related Articles

Ludwig W. Tamari (1927-2017) lived a full life.In fact, he lived an exemplary life.

The Great War and the Remaking of PalestineSalim TamariUS: University of California Press, 2017Pp.

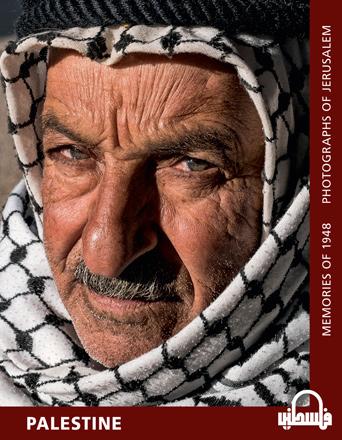

Palestine: Memories of 1948, Photographs of JerusalemChris Conti and Altair AlcantaraTranslated from French by Isabelle LavigneLondon: Hespe