You are here

The thwarted desire to belong

By Sally Bland - Feb 22,2015 - Last updated at Feb 22,2015

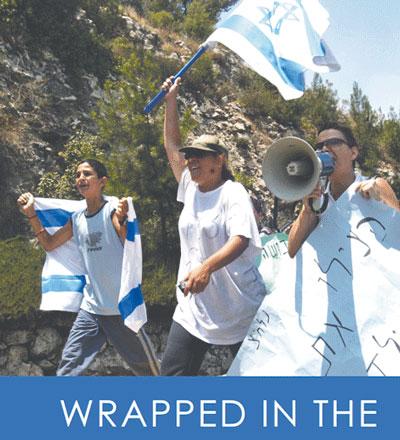

Wrapped in the Flag of Israel: Mizrahi Single Mothers and Bureaucratic Torture

Smadar Lavie

New York-Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2014

Pp. 202

While the title of this book suggests that it covers a single topic, nothing could be farther from the truth. In the process of explaining why it is virtually impossible for Mizrahi single mothers to provide a decent life for their children, Smadar Lavie analyses multiple aspects of the Israeli state, economy and society, and also shows the interplay between Israel’s domestic politics and its conflict with the Palestinians. She masterfully connects the dots between a wealth of detailed facts to point to strategic issues that are often overlooked in the daily barrage of reporting on Palestine/Israel.

“Wrapped in the Flag of Israel” is unique in a number of ways. It is the first English-language ethnography on single motherhood outside North America. Also unique is Lavie’s interweaving of personal experience and research into an engaging narrative that jumps from social science terminology to slangy, diary style. Herself both an Israeli Mizrahi single mother and activist, who has stood in the welfare lines, and a US-trained anthropologist, she brings these seemingly divergent perspectives to her analysis. Her unflinching exposure of intra-Jewish racism and its political consequences is unmatched.

The book’s title is both very concrete and highly symbolic. It refers to Vicky Knafo, “a 43-year-old single mother of three”, who on July 2, 2003, began a 205-kilometre march from Mitzpe Ramon, an isolated Mizrahi town in the Negev Desert, to Jerusalem, literally “wrapping herself in the Israeli flag”. (p. 1)

Knafo was protesting the state’s decision to slash the already meager welfare allowance of single mothers. Many others got involved, including the author, setting up a tent city in a Jerusalem park which lasted for over a month, until a suicide bombing refocused attention on the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. This is one of many examples cited by Lavie to show how the Israeli establishment can and does use — and sometimes creates — security concerns to override the Mizrahi struggle for equality, and preclude a potential Mizrahi-Palestinian alliance.

There are many ironies involved in the Mizrahi situation. Unlike 1948 Palestinians or, say, American Blacks, who have organised for minority rights, Mizrahi (Eastern) Jews constitute the majority of Israeli citizens. They are also the majority of the poor and disenfranchised, though official discourse disguises these facts.

Due to a particular combination of gender and racial discrimination, the vast majority of welfare moms in Israel are Mizrahi. Lavie gives a vivid, but troubling account of the status of Mizrahi women from the early days of Zionist settlement through the 1960s. By virtue of their Arab origins, they were regarded as backward, and trapped on the lower rungs of society by the Ashkenazi elite, who headed the colonisation of Palestine.

Yet, ironically, in their desire to fit into the Israeli/Jewish mainstream, Mizrahi deny their Arab roots and the history of discrimination against them. In turn, “the regime uses this false unity to mask how it uses bureaucracy to crush, marginalise, contain and buy out individuals or groups within social protest movements.” (p. 80)

This point is the political crux of the book which “explores the conundrum of protesting against a state one is strongly obliged to deeply love”. (p. 19)

In Lavie’s view, the state’s manipulation of Mizrahi loyalty rules out any real agency on their part.

Lavie underpins her contention of bureaucratic torture by analysing a range of legal, economic and social factors that hinder single mothers getting a job with a living wage or public assistance. Especially the privatisation drive in the 1990s, which brought rampant inflation, skyrocketing rents, reduced social benefits and imported labour, exacerbated the labyrinth of hurdles to be overcome. The single mother suffers endless waiting in line, shuttling between government agencies, often with her children in tow, in order to fulfil changing criteria and demands for various documents.

In the end, she is often refused aid, but she has no choice but to keep try trying. If she can’t provide for her children, they will be forcibly enrolled in a boarding school, even though this costs the state seven times more than granting the mother assistance — only one example of bureaucracy’s illogic. This vicious circle is not merely irritating but inflicts serious pain and often leaves the single mother with real psychological and physical ailments. Her ability to cope may “disintegrate because she uses herself as a human shield to shelter her children from forced boarding, homelessness, lack of medical treatment, etc”. (p. 109)

Provocative at every turn, Lavie ends with a question whose answer could have a major impact on future developments: “How long can the regime depend on Mizrahi docile loyalty to the Jewish state?” (p. 152)

Related Articles

On the Arab-Jew, Palestine, and Other DisplacementsElla ShohatLondon: Pluto Press, 2017Pp.

Companions in Conflict: Animals in Occupied PalestinePenny JohnsonBrooklyn-London: Melville House, 2019Pp.

With persuasive logic, an acute sense of irony, and a keen eye for injustice, Piper Kerman hosts the reader for a year in a minimum security federal prison.