You are here

Scholar explores impact of Levantine earthquake of 418/419 AD

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Oct 13,2021 - Last updated at Oct 13,2021

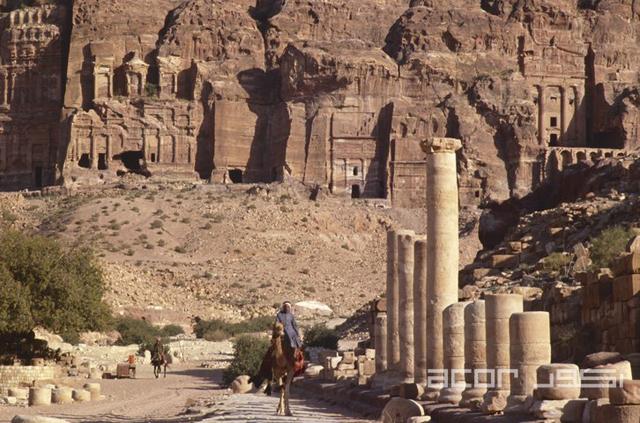

The earthquake of 418/419 AD was allegedly responsible for ending the Late Roman/Early Byzantine occupation of Al Zantur, the large Nabataean residence, on the hill behind the Great Temple in Petra (Photo courtesy of ACOR/Jane Taylor collection)

AMMAN — Conclusions about an earthquake that damaged “many towns and villages in Palestine” in 418/419 AD came from the ancient chronicler, Marcellinus Comes, who died in 534 AD, noted an American archaeologist.

“The geological evidence is somewhat ambiguous, as well, in part because another large earthquake happened in 363 AD, and it’s difficult to distinguish geological [and archaeological] evidence from events only a half-century apart,” said Ian Jones from University of California, San Diego.

He said that researchers are probably looking at a much smaller impact than previously suggested for the earthquake of 418/419 AD.

“It would certainly have affected Jerusalem and its surroundings, but the earthquakes affecting southern Jordan would have been earlier than 419AD,” Jones said.

Regarding the magnitude of the earthquake, some researchers have tried to suggest magnitudes and epicentres, but these suggestions were based on archaeological identification of destruction layers, he said.

As far as the significant monuments that were destroyed, it has been suggested that the earthquake was responsible for ending the Late Roman/Early Byzantine occupation of Al Zantur, the large Nabataean residence, on the hill behind the Great Temple in Petra.

In Jerusalem, though, it was very likely that the earthquake of 418/419 AD caused damage, the archaeologist elaborated.

“Another large earthquake struck 50 years earlier, in 363 AD, and the Byzantine Empress Eudocia sponsored rebuilding of the city’s walls in the mid-5th century,” Jones said.

Regarding numismatic evidence, coins can only give us additional information about the time period, he said.

“If we were lucky enough to have a destruction layer containing a coin precisely dated to 417 AD, we could say with some certainty that the destruction happened after 417 AD, but without more information we couldn’t necessarily say how long after,” Jones said.

One problem is that across the Eastern Mediterranean many coins seem to have been minted in the 4th century, but fewer were minted in the 5th century, Jones said.

“If we’re aware of these limitations and other factors, coins can be a very powerful tool in archaeology,” Jones said.

Related Articles

AMMAN — The ancient city of Gadara (modern Umm Qais) was developed during the Hellenistic and Roman eras and was part of the Decapolis

AMMAN — “We do not possess enough primary sources about the contribution of the copper mining sector to the economy of the Ayyubid-Mamluk dy

AMMAN — During an excavation work carried out by the German-Danish team in Jerash, remains of a building constructed on the bedrock and dest