You are here

Child labour among Syrian refugees a phenomenon, but London conference holds hope for them

By Mohammad Ghazal - Feb 29,2016 - Last updated at Feb 29,2016

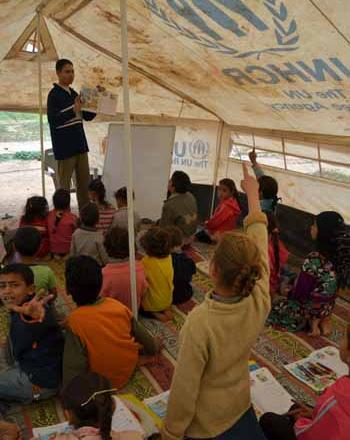

In this photo taken in January 19, at Zaatari Refugee Camp, children are seen pushing wheelbarrows (Photo by Hassan Tamimi)

AMMAN — Maya, a 13-year-old Syrian refugee residing in Zaatari camp, used to wake up every day at around 6am and sometimes before, but not to have breakfast and to go to school like other girls of her age.

Maya, not her real name, used to get out of bed to join her father and brother in working in nearby farms in Mafraq by illegally crossing the fence surrounding the camp, for a daily JD5 salary.

She would unlawfully leave the camp, in Mafraq, several times and work for months with her father and 12-year-old brother to help her family of six.

She worked every day from around 6am to 6pm and would return to the camp through the same spot in the fence in the darkness.

One day, Maya told her mother she did not want to go to work anymore. She refused to talk to anyone, cried most of the time and was acting differently. All of which alarmed her mother, who sought the help of one of the relief agencies working in the camp.

The relief worker that counselled Maya told The Jordan Times that she was sexually harassed by a guest labourer while working on one of the farms.

“Her parents were not convinced in the beginning, but after conducting medical tests that proved she was sexually assaulted, they stopped sending her to work," the relief worker said.

Her mother said the family was in dire need for money and was forced to send Maya and her brother to join their father in working in some farms nearby. “Each made around JD5 per day, but it was seasonal,” she told The Jordan Times.

“All families here send their children to work either inside or outside the camp if they can although it is risky and dangerous,” the mother said.

Maya and her brother are among thousands of Syrian children whose families’ difficult economic situation forces them to work to secure a source of income.

“Child labour among Syrian refugees is a big problem inside and outside the Zaatari camp,” Andrew Harper, the UNHCR representative to Jordan, told The Jordan Times over the phone.

“As it is difficult for Syrian families to find employment legally, they send their children to work and make them drop out of school to make some money,” he said.

“Around 30 per cent of the camp’s 80,000 residents are children of school age. Half of them do not attend any of the nine schools in the camp because they work,” Harper said.

Addressing the problem of child labour and preventing any sort of violations that Syrian kids might be subject to partially lies in the implementation of the international community’s pledges to Jordan during the recently-held donor conference in London to facilitate creating jobs for Syrians and legalising their work in the Kingdom, the UN official said.

Following the London conference, the government said it intends to designate five development zones and provide them with incentives under the new investment law. The EU also pledged to accelerate plans to revise preferential rules of origin with a view to an outcome by this summer.

These measures could in the coming years provide about 200,000 job opportunities for Syrian refugees while they remain in the country, contributing to the Jordanian economy without competing with Jordanians for jobs.

“When jobs are created for Syrian refugees, they will have a sense of security and will not send their kids to work and face risks outside their homes in illegal jobs,” Harper said.

According to Harper, the number of Syrian refugees escaping the fence to work outside the camp “used to be higher but the number has been reduced due to tight control on the fence”.

Child labour among refugees is growing at a fast pace and is turning into a phenomenon inside and outside the camps, Ahmad Awad, director of the Phenix Centre, told The Jordan Times.

A study released in late 2015 indicated that child labour is becoming “increasingly common” in Jordan, especially among refugees whose children join the labour market to help their families generate an income.

The majority of Syrian children working do not receive “fair” wages, as what they are paid is below the minimum monthly wage specified for Jordanians — JD190 — and guest workers — JD150. According to a study by Tamkeen for Legal Aid and Human Rights, around 46 per cent of Syrian boys in the workplace put in more than 44 hours a week, while girls make up 14 per cent of the total number of Syrian children in the labour market.

Legalising Syrian workers and creating jobs for Syrian parents would play a significant role in curbing child labour, Awad added.

“If Syrians are given the chance to work in decent conditions in return for monthly salaries, they will definitely become economically and socially stable and will send their children to schools,” he said.

Manal, a Syrian refugee who fled to Zaatari three years ago from Daraa after her husband was shot dead, said that she is “willing to work long hours and learn any skill to be able to work legally”.

“I heard about Jordan’s plans to create jobs for Syrian refugees and that it would not be at the expense of jobs for Jordanians. I think this is a very good idea as we are in dire need for money,” she told The Jordan Times.

“If I have a job, I will send my children to school because I know their future is in education and not in cleaning shops or carrying stuff for other people in the marketplace,” said Manal.

Economist Hosam Ayesh said that the international community needs to speed up the implementation of its pledges to Jordan to be able to create some jobs for Syrians, as that will play an important role in ending child labour.

“We need to be realistic that the jobs may not be created in a short time. It will be a gradual process, but it will eventually and partially help,” said Ayesh, adding that engaging Syrian families in some economic activities or small-scale projects will help as a start.

Conducting awareness programmes among Syrian families, financially enhancing their conditions and reducing university tuition for their children are crucial to addressing child labour, said Harper.

“There is a need for more efforts to address the gap, as there is a big problem when it comes to the thousands of Syrian youngsters not enrolled in schools, which will result in high illiteracy rates in the future,” Harper added.

“Currently, we have a partnership with Al Bayt University whereby Syrian refugees are given the chance to study and pay tuition similar to Jordanian students rather than as foreigners,” the UN official said.

“Many Syrian teenagers refuse to go to school because they feel there is no point. Universities can obtain support from the international community if they do this and take the initiative as there is large room for attracting aid in this area,” Harper said.

If the UN estimates are correct and refugees would stay for 17 years in their haven, Maya and her brother might enroll in Al Bayt University, if they are guaranteed schooling and a decent living for the family.

Related Articles

From his precious savings, Syrian Khaldoun Al Ahmad decided to spend JD20 to buy a tent and transform it into a school for fellow refugees at a makeshift camp located in the Northern Jordan Valley.

As the Syrian crisis marks its third anniversary this weekend, 400 to 1,000 Syrians continue to cross into Jordan every day, fleeing the war in their country, according to the UNHCR.

TRIPOLI, Lebanon — When 13-year-old Mounir fled Syria for Lebanon with his family after surviving a rocket strike that nearly killed them, h