You are here

Danish scholar pores over ancient ceramics, pottery

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Jan 02,2018 - Last updated at Jan 02,2018

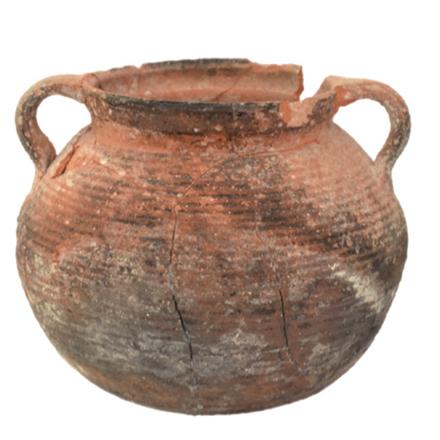

A typical Late Roman cooking pot, 3rd century AD (Photo courtesy of The Danish-German Jerash Northwest Quarter Project)

AMMAN — Though common ware pottery have been found in great number at classical excavations throughout the world, little attention has hitherto been paid to the ceramic group, according to a Danish archaeologist.

“The ceramic group, I believe can prove to be of great importance to the archaeological material, in spite of its plain and simple exterior,” said Signe Bruun Kristensen, from Aarhus University, Denmark, who is a part of the Danish-German Jerash Northwest Quarter Project.

According to Kristensen, the Late Roman and Byzantine period in Jerash was an era of prosperity: “Jerash saw an increase in population, building activity and subsequently a growth in material production — correspondingly in ceramics.”

During the excavations conducted by the Danish-German Jerash Northwest Quarter Project, a great number of ceramic material has been found, the scholar noted.

“As the common ware pottery includes domestic shapes, such as pans, cooking pots, casseroles, plates and bowls, it has been an active part of everyday life for the residents of Jerash in the Roman and Byzantine periods. Thus, an important element in the archaeological research and a notable tool for illustrating everyday life of ancient Jerash,” Kristensen told The Jordan Times in a recent e-mail interview with.

Moreover, the recent excavations have discovered some domestic buildings, laying bare a large amount of intact vessels of different types, predominantly locally produced common ware and cooking ware, she said.

The ceramic group is, as is the case today, present in every household not conditional of social class, therefore allowing archaeologists a glimpse into the ancient kitchens and workshops of Jerash, Kristensen elaborated.

“The locally produced pottery of Jerash follows the production traditions of its neighbouring regions,” the Danish archaeologist explained, adding that the excavated ceramic material discloses a great variety of vessel shapes and colouration in the fired clay and decorations.

“The shape of the vessels can guide us to an immediate function of the vessel, the firing of the clay [the colouration] can help date the period in which the vessel was produced, and additionally put into use,” Kristensen noted.

“The bright orange colour is common in the Roman period, the deep reddish is mainly seen in the Late Roman period, and the bright grey dominant of the Byzantine period,” the archaeologist explained.

The potters again provide us with information about their high level of craftsmanship, by demonstrating their ability to regulate oxygen and temperature in the kilns thus controlling the outcome of the colouring and expression of their product, she said.

“One of the ceramic approaches used by The Danish-German Northwest Quarter Project is thin-section analysis,” Kristensen said. “A technique registering the different components of the clay, providing us with the possibility of establishing whether the clay [and therefore the pot] was made of locally collected clay or should be categorised as an import.”

“This method furthermore enables us to examine if the local potters intentionally improved the clay for production purposes,” she continued, adding that “the improvements could be made by adding elements, such as quartz particles to the naked clay, and thereby improving the heat fluctuance of the cooking pot — a method actively used in the Roman provinces of the main land”.

The clay matrix of the ceramic vessels of Jerash show no sign of “artificial” clay improvements she said, instead, the potters have adapted the shape of the pot to improve the function.

“The soft curves of the vessel reduce the risk of breakage when using the vessels over fire,” the researcher noted.

Related Articles

AMMAN — From the Roman period to Early Islamic times, Jerash had a “strong and continuous” pottery production, according to two scholars who

AMMAN — Coming to Jordan for the first time in 1975-1978, Ina Kehrberg-Ostrasz joined the excavations at Teleilat Ghassul (five-six ki

AMMAN — A Danish-German project is attempting to address the problem of poorly-documented mediaeval material found at sites like Jerash with