You are here

Exploring archaeological wonders of Jordan

By The San Diego Union-Tribune (TNS) - Jan 25,2018 - Last updated at Jan 25,2018

Photo by Amjad Ghsoun

In Jordan’s extraordinary rose-red “Lost City” of Petra, I have just huffed up 700 zigzagging stone-carved steps to the ancient mountaintop High Place of Sacrifice with its sacred altar and goat blood drain. And now, along a dirt trail, I rest in a rug-draped souvenir stall while an octogenarian bedouin woman — who is traditionally clad in a long embroidered madraga dress and grew up in a cave — deftly strings a fragrant necklace of dried cloves to sell me.

Way down below, camels with tasselled bridles emit rumbling, dinosaur like roars while being led by robed bedouin tribesmen whose eyes are rimmed in jet-black kohl liner. Other indigenous bedouins, headscarves atop their flowing ringlets, strangely resemble Johnny Depp’s Jack Sparrow as they trot on donkeys (“you want air-conditioned taxi?”) past monolithic, 2,000-year-old tombs.

Mystical, mind-blowing Petra literally rocks. Around the 1st century BC, the now-extinct Nabataean people ingeniously chiselled the capital of their Arab empire from sheer sandstone cliffs; at times 30,000 inhabitants bustled about the affluent metropolis that was a major trade stopover for incense- and spice-toting camel caravans. Stretching across harsh desert terrain (Petra’s archaeological park encompasses 264 square kilometres), the once-forgotten marvel includes intricate temples; obelisks honouring pagan gods; etchings of snakes, lions and eagles; cave dwellings; a theatre; and more than 600 massive burial chambers, all hewed from soaring rock faces that bewitchingly glow in swirling hues of terra cotta, apricot and blush pink.

“Petra is one of the world’s biggest mysteries,” says Omar, my Jordanian guide with Exodus Travels. “There is no record of history. And 65 per cent of Petra is still underneath our feet, hidden by dust.”

For almost two weeks, I traverse much of Jordan by bus with Exodus, an adventure company that also brings us 16 intrepid voyagers to the less-visited far reaches of this Middle East nation. Petra is Jordan’s primo tourist draw, but elsewhere we are the only ones clambering over archaeological ruins of a mosaic-splashed Roman fort and a Muslim dynasty’s frescoed castles in no man’s land. History mixes with the present — driving through the bleak parched desert, we pass a sprawling Syrian refugee camp housing 36,000 in rows of white shelters; Jordan has taken in about 1 million people who have fled the war-torn nation to its north.

Before joining our group, I spend two days in the vibrant old quarters of capital Amman and clearly stick out — locals repeatedly ask where I am from. This is a Muslim country, and when I say “America”, they all warmly reply, “Welcome to Jordan,” often with their hands placed over their hearts. I am probably welcomed 100 times — in taxis, cafes while I eat mezze plates of hummus and falafel, shops, hookah bars, streets lined with bowing worshipers outside a minaret-topped mosque.

It is the start of a cultural odyssey. With Exodus, I also retrace exploits of Lawrence of Arabia, the dashing British officer who gained fame in World War I for leading the legendary Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Turks. Pre-trip, I rewatched the 1962 Oscar-winning epic “Lawrence of Arabia”, so it’s eerie to stand in the gravely quiet courtyard of Qasr Al Azraq, the storied black basalt fortress where T.E. Lawrence and his bedouin troops plotted attacks during the winter of 1917.

Another day, I am bouncing in the blanketed bed of a bedouin-driven Toyota pickup tearing across the UNESCO-listed Wadi Rum desert, nicknamed “Valley of the Moon” for its rippling peach-pink sands pierced by titan sandstone and granite peaks. Lawrence and his guerrilla rebels made their base here in 1917-18, and decades later director David Lean filmed the cinematic classic in this otherworldly locale. (Planetwise, Wadi Rum also subbed for Mars in the 2015 Oscar nominee “The Martian”.)

Near a commemorative rock carving of Lawrence’s face, we stop at a rectangular tent woven from black goat’s hair and occupied by hospitable bedouins who offer us cardamom-and-sage tea. First, one of them has us stick out our forearms and rolls on a soaplike perfume. “It’s gazelle innards,” Omar says afterwards. Yuck.

Most of the bedouins I meet speak only Arabic, so Omar gladly translates. “He says, ‘You are a camel.’”

A what?

“It means you are beautiful, because camels are beautiful with their long eyelashes.”

I sit my hump down and enjoy the steaming sweet tea, cooked in a charred brass kettle over a rudimentary fire pit. Because Muslims avoid alcohol, tea is a main social drink in Jordan, and you’re constantly offered a cup in friendship. (You’ll find non-alcoholic beers and non-alcoholic wines on some menus, but the rare place I hoist a glass of Cab is outside Petra’s gate at the 2,000-year-old Cave Bar, touted as the world’s oldest saloon. Indeed there are spirits; it’s a former Nabataean family tomb.)

In Wadi Rum, I sleep inside a goat-hair tent in a rustic bedouin camp set against wind-buffeting cliffs on the desert floor until at 4am I am awakened by a distant muezzin’s melodic call to prayer and, after that, a rooster’s shrill cock-a-doodle-doo.

Next I wake up the entire camp shrieking as I clumsily mount my ride. “Yalla, yalla,” Rashid gently urges his herd of five sibling camels, meaning “Let’s go,” and soon with just one other traveller, we have the pre-dawn moonscape to ourselves.

Atop cud-chewing Aliya, I hypnotically watch the flaming sunrise turn the unending vastness a radiant gold. For 90 beyond-belief minutes, the only sounds are the camels’ feet softly sinking into the powdery dunes and the chirping of Sinai rosefinches. A well-fed stray dog joins our pack, funnily bringing up the rear.

Every day of our itinerary, we hit an archaeological treasure. I feel like I’m in Italy as I wander the immense 2,000-year-old Roman city of Jerash, dubbed the “Pompeii of the Middle East” for its well-preserved ruins buried by blown sand for centuries. Cultures humorously collide: Two bedouins, head-scarfed with red-and-white chequered keffiyehs, toot “Yankee Doodle Dandy” on bagpipes in the Corinthian-columned amphitheatre near the chariot hippodrome.

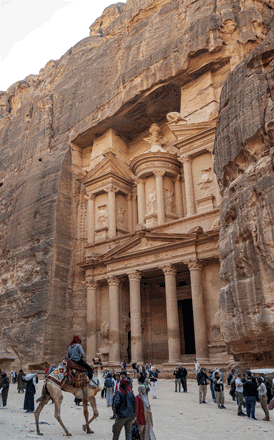

Petra, though, is the jackpot. Abandoned in the seventh century, it was rediscovered by a Swiss explorer in 1812 and became a UNESCO heritage site in 1985. Hidden away, to get to the ancient city, you have to trek through the dramatic narrow Siq, a nearly mile-long slot canyon sandwiched by 24-story-high veiny rock edifices and at times only three metre wide. Nature-created formations stare down in the shapes of elephants and skulls. At the end, the Siq cracks open to reveal the grandstanding, rock-whittled funerary-urn-crowned Treasury, likely a former temple. Harrison Ford galloped up to the fantastical facade in the 1989 movie “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade” in search of the Holy Grail.

After dark, I return for the corny-cool “Petra by Night” ceremony. Even with my flashlight I can barely see as I stumble through the ghostly Siq, lit only by hundreds of luminaria candles, and then sit in the luminaria-lit dirt in front of the shadowy Treasury. Bedouins play a flute and rababa string instrument before the big reveal — spotlights suddenly bathe the Treasury in changing psychedelic colours.

Over two days I walk 37 kilometres in Petra because the scenes won’t quit. On the High Place of Sacrifice climb, I smell the pungent smoke of juniper branches, and soon a bedouin man is hawking me a morning shot of Arabic coffee heated by a campfire teetering on a killer-view ridge. Later, as my elderly new friend Hammadeh strings that clover necklace in her ramshackle stall, she tells me through interpreter Omar how she once lived in a cave in Petra and still follows the old ways, herding her sheep and goats. Without tourism, she frets, she has no money. “I thank God. I thank God for everything,” she says as I buy three more necklaces.

Petra’s most jaw-dropping high place is the Monastery, accessible by hoofing up nearly 1,000 Nabataean-cut steep steps. After the path’s last bend, this mammoth stone temple — it’s 47 metres wide — magically pops out of a remote mountainside towering over my puny presence. From the monastery, I continue ascending a boulder-strewn trail until next to a grazing grey donkey I see a piece of scrap wood lying against a pile of rubble and hand-scrawled, “Welcome to Top of the World Café.” Up further, I reach the “café”, a tattered, tented platform precariously perched over a rocky ledge in the heavens. And there, a 17-year-old bedouin named Lost (“because you’re always found”, he smiles) offers me another cup of tea, this one with a sprig of mint.

Related Articles

PETRA — “Here, this is the gateway to the monastery, the most beautiful and famous monument of Petra,” said Abraham Mashaleh, 48, a Jordania

Residents of Um Sayhoun village in the south, and staff from the Department of Antiquities (DoA) and the Petra Archaeological Park (PAP) are now contributing to maintaining a World Heritage Site thanks to a UNESCO project.

Singapore’s Minister of State for Home Affairs and Foreign Affairs Masagos Zulkifli and an accompanying delegation visited the ancient Nabataean city of Petra on Thursday.