You are here

‘Grief as a virus’

By Sally Bland - Jun 19,2017 - Last updated at Jun 19,2017

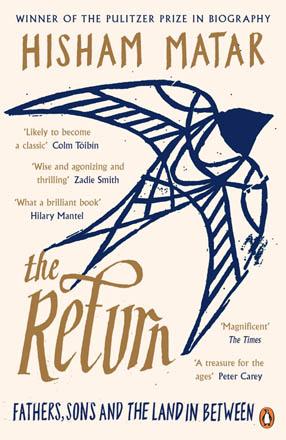

The Return: Father, sons and the land in between

Hisham Matar

UK: Penguin Books, 2017

Pp. 280

This is an intensely personal memoir, yet Hisham Matar reveals not only his innermost thoughts and feelings, but much about the history and culture of his native Libya. The bridge between the private and public aspects of the narrative is his search for his father, Jaballa Matar. Poet, military officer, diplomat and businessman, the elder Matar became a major opponent of Qadhafi’s regime, and was imprisoned and later “disappeared”.

The book opens in March 2012, as the author waits in Cairo’s airport, with his wife and mother, to fly to Benghazi, returning to Libya after 33 years. There he will reunite with his extended family, not least uncles and cousins who were with his father in prison, and follow other leads as to what happened to him. Along with anticipation, his ambivalence is palpable. He wants to return, yet he does not; he wants the truth, yet fears it.

Since his father’s letters stopped in 1996, the same year that 1,270 prisoners were killed in the notorious Abu Salim prison where he was being held, his fate has been unknown. His absence and the uncertainty involved has unsettled Hisham ever since, affecting his ideas on life and death, love, family and exile: “It turns out that I have spent all the time since I was eight years old, when my family left Libya, waiting… my bloody-minded commitment to rootlessness… was my feeble act of fidelity to the old country, or maybe not even to Libya but to the young boy I was when I left.” (p. 25)

Matar weaves an engrossing narrative that moves back and forth between past and present — often collapsing the two, between real events, dreams and contemplation, between hopes, self-doubt and fears. There are happy childhood memories and the

anguish of losing a father. There are strikingly beautiful descriptions of European as well as Libyan landscapes. There are vivid blow-by-blow accounts of the 2011 revolution as Matar follows it via cell phone from London, where he has lived most of his life. The day revolutionaries broke into Abu Salim, releasing the prisoners, Matar talked with a man who was hammering away at the steel doors of the prison. Hopes of finding his father rose once again, only to be dashed. One prisoner had a photo of Jaballa, but had lost his memory entirely.

Though emotionally perilous, Matar’s return produces precious cameos of Libyans like his cousin, Marwan, who was transformed by the revolution: “He went from being a prosecutor infamous for not being able to get out of bed before noon to one of the most energetic and articulate campaigners for human rights.” (p. 107)

Matar introduces his uncles, well-versed in literature, some of them poets. A portrait of his grandfather, who fought with Omar Al Mukhtar against the Italian occupation, highlights a chapter in Libya’s history that — aside from Moustapha Akkad’s film — has received scant attention in the West. There are many other examples of Libyans’ rich history and culture that have been obscured from world view, whether by Qadhafi’s suppression or the recent chaos.

Most compelling, however, is Matar’s frank admission of the deep psychological scars he has incurred: “We need a father to rage against. When a father is neither dead nor alive, when he is a ghost, the will is impotent.” (p. 34)

At the same time, he developed an acute sense of justice and awareness of the misuse of power: “Pain shrinks the heart. This, I believe, is part of the intention. You make a man disappear to silence him but also to narrow the minds of those left behind, to pervert their soul and limit their imagination. When Qadhafi took my father, he placed me in a space not much bigger than the cell Father was in.” (p. 246)

Reading such words, one might think that Matar let his life slide, but no. Inspired by his father’s integrity and productivity, he completed his education, became a literary scholar, university lecturer and successful author, though he mentions these things only in passing. Meanwhile, he mounted a sustained campaign demanding information about his father and his release, along with other political prisoners.

Yet these accomplishments do not assuage the anger, guilt and sense of absurdity that coloured all his relationships and experiences: “Rage, like a poisoned river, had been running through my life ever since we left Libya. It made itself into my anatomy, into the details. Grief as a virus.” (p. 119)

Perhaps most of all, he grapples with hope, following up any hint, however fragile, that his father might still be alive, yet, fearful that he cannot survive more disappointment, or never knowing the truth for certain.

The Return is a hauntingly beautiful book because of Matar’s deeply sensitive prose. It is also haunting in a negative sense because his father’s fate remains unresolved, and the cruelty involved in his case was meted out to so many. Matar does not pretend to draw grand conclusions; in fact, it is his total lack of pretentiousness that makes the book so genuine and compelling. Still, it could be interpreted as saying that although justice does not always win out, one must keep fighting for it, if life is to have any value.

Related Articles

In this novel, Hisham Matar portrays the impact of state and social repression on the human psyche, interpersonal relations and family dynamics in particular, through the eyes of a young boy.

Muammar Qadhafi’s son Saadi, his special forces commander who fled abroad during Libya’s 2011 revolution, was imprisoned in Tripoli on Thursday after Niger agreed to send him back from house arrest there.

Gaza as a MetaphorEdited by Helga Tawil-Souri & Dina MatarLondon: Hurst & Company, 2016Pp.