You are here

King Hussein’s legacy revisited

By Sally Bland - Oct 04,2015 - Last updated at Oct 04,2015

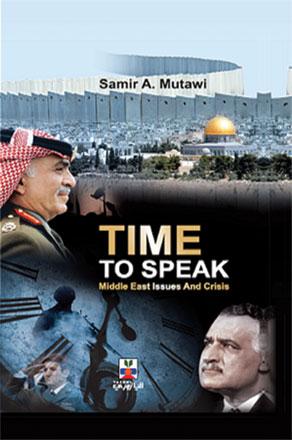

Time to Speak: Middle East Issues and Crisis

Samir A. Mutawi

Amman: Al Yazori Publishing House, 2014

Pp. 225

“Time to Speak” is a collection of lectures and papers delivered by Jerusalem-born Dr Samir Mutawi over the past 20 years. The timeline of the subject matter is even longer, reaching back to the 50s and extending into the 21st century. The primary focus is on how Jordan weathered the many stormy events of this period, and the factors that guided its decision making.

Mutawi’s career qualifies him to speak with authority: After working as a journalist in the UK for 30 years, he returned to Jordan and served as King Hussein’s chief of press, research and studies, and official spokesman at the Royal Court. He also served as information minister, Jordan’s ambassador to the Netherlands, chairman of the board of Jordan News Agency, Petra, and professor of international studies at Philadelphia University.

Much of the book is actually a tribute to the late King Hussein whose leadership Mutawi regards as having been wise, courageous, energetic and consistent. While King Hussein’s legacy is often described as his successful building of the modern nation of Jordan, Mutawi takes this a step further, regarding the late monarch as a “national Unifier… Whereas in 1953, a man might identify himself as a Circassian, a Palestinian, or a Bedouin of a certain tribe, Jordan’s peoples today almost universally refer to themselves as simply Jordanian”. (p. 19)

The other aspect of King Hussein’s legacy highlighted in the book is his prominent role in the search for peace in the Middle East.

Many chapters of the book demonstrate how closely intertwined are Jordan’s domestic and foreign policies. This is partly the result of the country’s geopolitical position, but also due to King Hussein’s self-image as a Hashemite and thus inheritor of the traditions of the Great Arab Revolt, making him “believe that his duty was not restricted to a purely national actor role but as one who encapsulates a larger Arab role”. (p. 45)

This Arab role was a major factor in King Hussein’s decision making, a process that is high on the list of concerns as Mutawi examines the factors influencing Jordan’s abiding involvement in the Question of Palestine, its participation in the 1967 war and, later, its position during the Gulf Crisis of 1990-91.

Highlighting King Hussein’s “marathon diplomacy” — visiting over a dozen countries in the space of a few weeks, Mutawi calls the immense efforts exerted by Jordan to avoid the 1991 war on Iraq as “one of the most unsung uphill political battles of recent memory”. (p. 65)

Part of Mutawi’s motivation for writing is countering misperceptions about Jordan in the Western media; another part is analysing how regional players have interacted — or clashed with each other, whether in the various attempts at Arab unity, or the recurring wars with Israel. Throughout the period under study, Mutawi’s view of Jordan’s overall role is that of regional stabiliser, balancer and harmoniser.

In another chapter Mutawi mounts a particularly scathing critique of Elie Wiesel’s massive advertising campaign to woo President Obama for the Israeli position on Jerusalem. Besides setting out the justice of Palestinian, Arab, Christian and Muslim claims to the city, Mutawi cites the arguments of Israelis who are critical of their government’s policies.

The same applies to his writing on the Apartheid Wall, which he studied firsthand from north to south when asked to prepare a paper for the Jordanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs as background for a legal submission to the International Court of Justice in The Hague. His account is both incisive and heart-rending as he describes the devastating effects of land confiscation, settlement building, the closure system, etc. on Palestinian lives. “What I saw in the West Bank and East Jerusalem, my birth city, exceeded my worst expectations.” (p. 121)

Many other topics are covered such as how King Abdullah II is building on his father’s legacy to develop Jordan’s economy and bring it into the era of globalisation and rapid technological advance. A seemingly divergent chapter is a study examining presidential rule and foreign policy under Egyptian president Nasser (1952-1970), but this ties in with Mutawi’s special interest in the decision-making process.

A final chapter compares how Arab media have approached the Arab-Israeli conflict before and after the 1967 war, returning to the days when radio was the preeminent mass media until being eclipsed by the satellite channels.

Related Articles

Bad Girls of the Arab WorldEdited by Nadia Yaqub and Rula QuawasAustin: University of Texas Press, 2017Pp.

The Jordanians and the People of the JordanKamel S. Abu JaberUK: Hesperus Press Limited, 2021, 159 pp.Although the late Dr Kamel S.

Winds of Change: The Challenge of Modernity in the Middle East and North AfricaEdited by Cyrus Rohani and Behrooz SabetLondon: Saqi Books, 2