You are here

Consequences of an earthquake: Historical chronology of Gerasa

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Mar 29,2024 - Last updated at Mar 29,2024

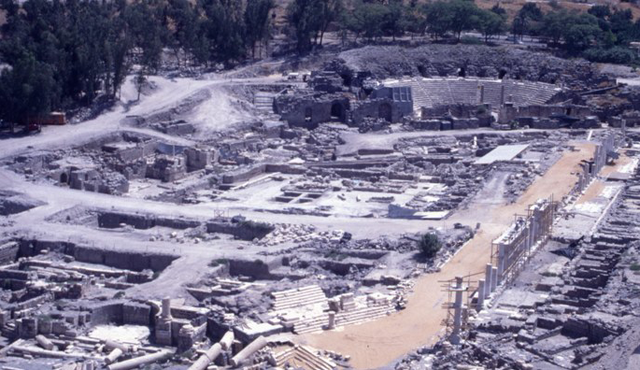

Agora in Gerasa. Agora was an open space of the city reserved for commercial, political, civic, religious and social purposes (Photo courtesy of ACOR)

AMMAN — Plagues, wars and earthquakes shaped the history of urban centres and states. Ancient Gerasa (Jerash) was subjected to a number of major disasters but none shook the town as much as the one in 749 AD.

Jerash became occupied around 8,000 BC, where the remains of a Neolithic mega-site have been excavated on Tall Abu Suwwan at the southern extent of the modern city. A Bronze and Iron Age settlement was centred on the southern parts of Jerash, but it has left no traces after the 7th century BC.

However, urban history starts around the 2nd century BC when Gerasa became part of a Hellenistic coalition of cities called “Decapolis”.

The town revolved around the Temple of Zeus and the Camp Hill and it saw an expansive building boom during the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, the peak of the Roman Empire. The most important monuments were built in that phase and Romanised city elites tried to present themselves as good Roman citizens.

“Some of the major building activities that took place at this time included the inauguration of the rebuilt Temple of Zeus in 163 AD; a series of fountains on the town’s axial street [also known as the Cardo] of which the Nymphaeum was the most elaborate; as well as the construction of the South and North Theatres, the Macellum, and the East and West Baths,” noted Alan Walmsley from the Macquarie University in Australia.

The Roman Emperor Hadrian visited Gerasa in the winter of 129-130 AD, and an inscription on the Triumphal Arch commemorates the imperial visit.

From the 4th to the 6th century AD, Jerash saw a drastic transformation of urban space in which new religious ideas as well as shifting economic priorities were accommodated within the built environment. Most importantly, the institutionalisation of Christianity and its inauguration as the state religion in the 4th century AD, brought the change. Logically, the pagan temples that were the focal point of the city were gradually abandoned and the construction of twenty churches and shrines took place.

“ The Temple of Zeus served as a stone quarry including a stone cutter’s workshop, in which building blocks were recut for use elsewhere in town,” Walmsley said, noting that other parts of the temple served as a metal workshop and as a dumping ground for waste products from a nearby ceramic kiln.

The Hippodrome became a centre for workshops and ceramic manufacture after its original purpose was changed during the 4th century AD

The transformation of Gerasa in the fourth to the sixth century entailed not only the repurposing of existing buildings, but also the reconfiguration of entire urban quarters, the historian continued, adding that the area south-east of the Temple of Artemis, for example, was redeveloped to accommodate the construction of a massive church complex comprising the Cathedral, the church of St Theodore, the Fountain Court, the Clergy House and a bathhouse constructed in 454–455 AD by Bishop Placcus.

“The bathhouse probably replaced an earlier bathing facility located to the east, which was now used for the manufacture of glass and another nearby building was repurposed to accommodate the fitting of an industrial-sized stone-saw,” the historian said, stressing that in the north-west and south-west districts, new streets were laid out according to the Roman-period grid system.

The Persian and Arab conquests of Jerash in 602 -630 AD and 634 AD did not have a negative impact on Gerasa as the 7th century appears to have been a time in which financial investments into the urban fabric went towards maintenance rather than building anew, Walmsley underlined, adding that the Arab conquest in 634–638 AD not only brought about a change in rulership, but also the arrival of Islam.

“With the consolidation of the Umayyad Caliphate [661–750 AD], the impact of the new governmental and religious agendas began to manifest themselves within the urban centres of the caliphate. The introduction of a new imperial religion had no immediate impact on the material culture of Jerash’s Christian communities. On the contrary, evidence of the careful removal of figural representations in the mosaic floors of some [but not all] of Jerash’s churches confirm the continuous usage of these religious buildings into the first half of the 8th century AD,” Walmsley elaborated.

The Early Islamic period is marked by the expansion of artisan quarters and artisan production as well as building of a congregational mosque in the 8th century.

“The mosque replaced a bathhouse, which had been in use from the 4th century until its increasingly advanced state of disrepair led to it being discontinued and the building eventually dismantled to make way for the construction of a mosque,” Walmsley said, adding that Jerash’s congregational mosque was based on the layout of the Great Mosque in Damascus, which was built in the first half of the 8th century AD in the reign of the caliph Al Walid (ruling between 705 AD and –715 D).

Walmsley maintains that a construction of the congregational mosque took place between 724 and 743 AD. However, the earthquake from 749 AD seriously damaged the mosque and other significant building in Jerash.

“The damage caused by the earthquake and the following discontinuation of structures is well-documented throughout Jerash and has led scholars to assume a total abandonment of the town — a sentiment that still lingers today,” Walmsley highlighted adding that the excavations within northwest Jerash have generally identified a discontinuation after the mid-8th century.

Some traces of the Abbasid-period occupation of the Macellum adds to the evidence as does pottery finds that suggest some continuous activity in the Temple of Zeus, however, the evidence for continuous occupation after 749 AD is by far the strongest in Jerash’s commercial and religious centre at the intersection of the two main thoroughfares and in the south-west district.

“Recent archaeological investigations in Jerash’s south-west district suggests that this area was crucial to maintaining the central functions of urban life and therefore, the financial investment in the restoration of the town and the efforts put towards reconstruction were concentrated here,” Walmsley concluded.

Related Articles

AMMAN — Built in the late 3rd or early 4th century AD, the Central Bathhouse in Gerasa (modern Jerash) was in use for another 300 year

AMMAN — Earthquakes have been the most devastating events that shaped the lives of civilisations and individuals during history.

AMMAN — When the Roman Emperor Hadrian visited Gerasa (ancient Jerash) in 129/130 AD, the Roman Empire was at its peak.