You are here

‘A story in every crack’

By Sally Bland - Jun 03,2018 - Last updated at Jun 03,2018

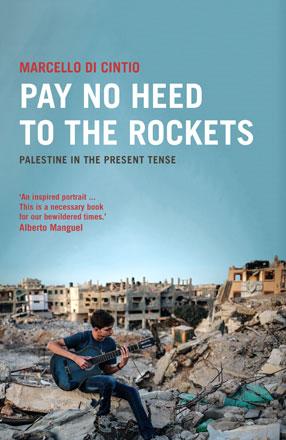

Pay No Heed to the Rockets: Palestine in the Present Tense

Marcello Di Cintio

London: Saqi Books, 2018

Pp. 221

The title of this book may be familiar to many as a quote from Mahmoud Darwish on how to brew a perfect cup of coffee during Israel’s 1982 siege of Beirut, but it refers to more than coffee. Darwish was insisting on his right to create and to savour the good things in life despite the persistent, looming violence. Adopting this theme, Canadian author Marcello Di Cintio takes the reader on a literary journey to see how Palestinians living under occupation and siege today find the inspiration to keep on writing, despite, or sometimes because of, adverse circumstances.

Di Cintio is well versed in Palestinian literature, and he starts off by exploring ideas expressed by Mourid Barghouti, as well as the legacy of Ghassan Kanafani and Darwish. In a smooth blend of the personal and the political, he intertwines their literary careers with biographical details, recounting pivotal incidents, especially the Nakba. In the same way, he contextualises the work of the newer writers he encounters on his 2015 trip to Palestine in their lived experience of occupation, discrimination and siege. Due to his familiarity with the Palestinian cause and literature, he is able to ask interesting questions that, in turn, elicit interesting discussions and answers.

The author is looking for stories and he is not disappointed: “I found a story in every crack of this place.” (p. 212) The stories he relates are not only about literature, but also reflect Palestinians’ history, and their everyday lives, hopes and feelings about their homeland. He is also searching for beauty in an overall depressing reality. In fact, his journey and this book were inspired by photos he saw of a young girl in a green dress plucking books out of the rubble of the 2014 Israeli war on Gaza. Amazingly, he is able to locate her in Nuseirat camp in the Gaza Strip, and hear firsthand her reasons for rescuing the books.

From Ramallah to Nablus, Jerusalem, Haifa, Acre, Nazareth and Gaza, Di Cintio interviews writers and poets, men and women. Some of them are well known and widely published like Raja Shehadeh; others have become known more recently, like Atef Abu Saif; while still others are making their names now, such as Asmaa Al Ghul. Their backgrounds are quite diverse. Some have always lived in Palestine, while others first came there with the Palestine Liberation Organisation after the Oslo accords.

A major discussion topic between the author and the writers he meets is the connection between writing and personal experience, and whether, as Palestinians, their writing must always have a political message — whether they must be spokespersons for their cause. For a young writer in Jerusalem, opposition to the Israeli occupation is a given, and he sees it more important to address social ills and outdated traditions. Many whom Di Cintio meets are part of “a new generation of Palestinian writers that has jettisoned nationalistic flag-waving for domestic narratives”. (p. 136) In different ways, their work “challenges the Western perception of Palestinians as either stock victims or militants”. (p. 148)

For his part, Di Cintio’s vivid account of the extraordinarily talented writers he meets in Gaza challenges misconceptions of that place as a cultural backwater.

Still, the national cause remains central for some, such as former political prisoner and leftist Wisam Rafeedi, who wrote incessantly while in jail and explains how prisoners smuggled their writings to each other and to the outside world.

A meeting with Dr Sharif Kanaana about storytelling and folktales unexpectedly leads into discussion of Hamas’s attempt to ban the book, “Speak Bird, Speak Again”, in which Kanaana co-published with Ibrahim Muhawi 45 of the 1,500 old folktales he had collected. Di Cintio then meets with a writer whose novel was banned by the Palestinian Authority.

Libraries also figure into Di Cintio’s research as he visits the Prisoners’ Library in Nablus which houses 8,000 printed books and 800 notebooks from Nablus and Jnaid prisons; the Khalidi library in Jerusalem, which successive generations of the family have struggled to keep intact under Palestinian control; and the National Library of Israel which houses nearly 6,000 books looted from Palestinian homes during the Nakba. Other cultural venues are also explored: the Educational Bookstore in Jerusalem, the Tamer Institute for Community Education and the Gallery Café in Gaza, kept open by the untiring efforts of Jamal Abu Al Qumsan.

In conclusion, Di Cintio writes, “During my time among the readers and writers of Palestine, I found no life undarkened by the Nakba and the conflict it continues to bear. Yet, I found no life wholly defined by the conflict either. Palestinians may long for a justice long denied them, but they also long to marry and to see their children marry… The Palestinians live complete lives in their disputed space, regardless of all they’ve lost and continue to lose”. (pp. 211-212)

Related Articles

In the Wake of the Poetic: Palestinian Artists after DarwishNajat RahmanNew York: Syracuse University Press, 2015Pp.

A Map of Absence: An Anthology of Palestinian Writing on the NakbaEdited by Atef AlShaerLondon: Saqi BooksPp.

I Don’t Want This Poem to EndMahmoud DarwishTranslated by Mohammad Shaheen US: Interlink Books, 2017Pp.